A sobering reflection on the state of human circumstances in 2025

In a world torn between progress and belief, this reflection explores why humanity may be more divided—and more vulnerable—than ever before.

I don’t know whether the world has ever been in as much turmoil as it is today. Perhaps it has. History is filled with wars, plagues, collapses, and revolutions. But somehow, the chaos of our time feels different—more complex, more pervasive, and more dangerous.

I’ve been trying to pull myself back from the endless stream of news and headlines, to rise above the noise for a moment—not to escape, but to reflect. To ask: How did we get here?

What becomes immediately clear is that we didn’t arrive at this moment by accident, nor in one sudden leap. This has been in the making since the mythical moment the first human stepped out of the proverbial Garden of Eden—whether that garden was real or symbolic.

I don’t claim to be a historian. I’m not here to recount every turn of our long and winding human timeline. What I can offer is the perspective of one man—an observer fortunate (or perhaps doomed) to live in these times. A witness to both the kindness and the cruelty, the light and the darkness that humanity is capable of. For over fifty years, I have watched the world turn. I have seen revolutions of thought and regressions into barbarism. I have seen technology rise, and trust collapse.

And so, I offer these reflections not as conclusions, but as questions. Not to solve, but to name what I see.

We tend to isolate historical events—major or minor—so we can analyze them, draw conclusions, and search for explanations for the present. We want to make sense of what is happening and, if possible, prevent future disasters. Take World War II, for example. Entire libraries of commentary and scholarship have been devoted to uncovering the root causes of that cataclysm—an event that drowned the West in chaos and pushed the entire world to the edge of annihilation.

We want to make sense of what is happening and, if possible, prevent future disasters.

But at a deeper level, I find myself asking: Has human history followed a predetermined path?

Were the rise and fall of great empires—and the emergence of tyrants, prophets, and revolutionaries—inevitable? Or is it all random and chaotic, a result of an unseen entropy that governs human affairs without reason or purpose?

I believe how we answer that question is what ultimately divides us.

And perhaps, how we answer it also determines the direction we take from here.

Though it may be too broad a brushstroke, I find myself dividing humanity into two great camps.

Some of us believe we are completely alone. That there is nothing—and no one—watching over us. For these people, life is about survival, pleasure, ambition, and extending our time here by any means possible. Among them are those who believe we can transcend death through science, through technology, perhaps even become gods ourselves. Eternal life—whatever that means—is no longer the promise of religion, but the pursuit of code, machines, and biological manipulation.

Some of us believe we are completely alone. That there is nothing—and no one—watching over us.

The second group believes the opposite—that we have never been alone. These are the faithful. Some are silent, praying quietly in their homes or temples. Others speak loudly, evangelizing what they believe is the truth for all humanity. They, too, exist along a wide spectrum—from the radically righteous to the deeply humble.

It may sound dramatic, but I believe both groups, in their extremes, pose a threat to the future of our species. What we’re witnessing now—bloody wars, civil unrest, ideological extremism—are not just political crises. They are spiritual ones. Existential ones.

The factions within and between these worldviews are in a state of near-war—sometimes literally, sometimes ideologically. And the battlefield is not just out there in the world. It’s within each of us.

It is said that each of us can only absorb and process a finite number of people, events, and ideas at any given moment. Once we exceed this threshold of sensitivity, everything begins to blur. The world clumps together into a mass of noise and confusion—a state of incomprehensible chaos.

If we accept this, then paradoxically, things begin to make sense. We begin to understand why so many feel paralyzed. Why hopelessness spreads. It’s not because we are weak, but because we are overwhelmed.

But acceptance alone cannot save us from ourselves. We must still strive. We must still reach for clarity, meaning, and connection. I believe—perhaps naïvely—that the reader might agree with me when I say: the only way out is together. Each of us must step forward and join hands with fellow human beings—not in perfection, but in honesty. By sharing our hopes and disappointments, our questions and fears, we might begin to chart a path through the fog.

And just as we begin to sense the possibility of unity, the same old divisions return to the stage.

We fall back into the camps I described earlier: the technologists vs. the faithful, the dreamers of transcendence vs. the believers in salvation. Their differences, their mutual suspicion, their mistrust—these forces reassert themselves, almost instinctively.

And at that moment, it begins to feel hopeless again. The very act of trying to solve the problem seems to summon the problem itself.

What we have called peace throughout history, I’ve come to see as a fragile peace—temporary pauses between surges of chaos. Are we caught in a cycle of doom? Each new disaster seems to escalate further than the last, like a spiral tightening toward some final collapse.

All the evidence seems to point toward a singular conclusion: a slow, inescapable march toward extinction. Toward absolute hopelessness.

You may call me a desperate pessimist. But please—wait.

The dichotomy of good and evil is as old as human consciousness. It didn’t take our ancestors long to recognize that there are forces of creation and forces of destruction—forces of order and forces of chaos. Nearly every religion, every philosophy, and every society across history has formalized this struggle in some way.

The dichotomy of good and evil is as old as human consciousness.

And yet, the nature of these forces remains contested. We do not agree on what is truly “good” or “evil.” One group’s savior is another’s tyrant. One community’s truth is another’s blasphemy. And so confusion grows, and clarity slips away.

Even indifference has become its own plague—a symptom of exhaustion. Many are simply too tired to choose a side. Too weary to fight another ideological battle that leads nowhere.

And yet—there is something we all seem to recognize, whether we admit it or not: that life is better than death. That peace is better than war. That creating is better than destroying. That kindness is better than cruelty. A common core of values, simple and almost universal, runs through nearly every culture.

But we never start from there. We never build on that.

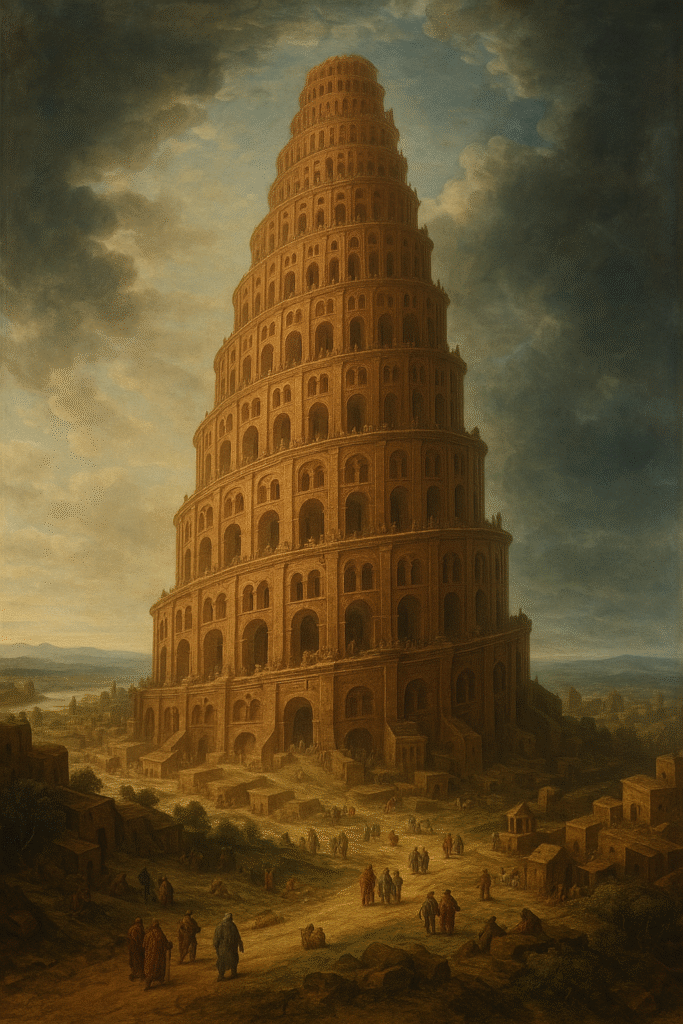

I want to draw your attention to an old story from the Bible—the story of the Tower of Babel. If we take the story at face value, it speaks of a time when humanity came together with a singular purpose: to build something magnificent. A monument to our shared identity. A celebration of what we are and what we can do when united.

But according to the story, a foreign force—portrayed as the Creator—intervened. By scattering our languages, by dividing our ability to understand one another, this force shattered our unity and ensured we would remain strangers to each other.

It was, in a way, the first schism.

The wound on the body of humanity that never healed.

And perhaps the real message is this: We don’t understand each other.

Let’s ask ourselves, who stands to benefit from our demise?